Oliver Stone's "Nuclear Now" makes no sense

The film ignores wind, water and sun, and covers up that civil nuclear energy, proliferation and bombs are inseparable

With Nuclear Now, Oliver Stone, has waded—with the self-assurance of an Oscar winner—into a field about which he knows next to nothing. Nuclear Now is based on a book Joshua Goldstein’s and Steffan Quist’s A Bright Future. The book is no better. Both the film and the book ignore the existential threats associated with nuclear technology that were already understood in 1945 and 1946. Nuclear Now also fails to consider well-developed alternatives for dealing with the unfolding climate catastrophe.

The following director’s statement is part of the Nuclear Now press kit:

Climate change has brutally forced us to take a new look at the ways in which we generate energy as a global community. Long regarded as dangerous in popular culture, nuclear power is in fact hundreds of times safer than fossil fuels and accidents are extremely rare.

Indeed, over the two decades from 1999 until 2020, fossil-fuel-fired electricity-generating power plants were across the world associated with 10 million premature deaths annually. It is not controversial that civil nuclear power has resulted in fewer such deaths. To equate that to safety is an example of the illogic that marks Nuclear Now. In fact, the movie is an elaborate example of the straw man fallacy. That is, the movie first creates a “fear! fear! fear!” caricature of the civil nuclear power opposition and then goes on to take down that caricature. The rest of this post discusses in detail what is swept under the rug both in Nuclear Now and A Bright Future.

Misunderstanding nuclear technology

The following is a small segment of an interview Stone did on the Joe Rogan Experience. The interview is part of the Nuclear Now public relations page. Referring to the making of the atomic bomb during Manhattan Project, Stone says:

As you know, it was misunderstood. At that point, nuclear energy was not a nuclear bomb. On the contrary, a bomb is very difficult to build and it takes a lot. It takes years, sometimes. It takes scientists, and they have to enrich the plutonium, and they have to work at it. There's all configurations in the bomb that don't exist in nuclear energy. So when people see a nuclear energy plant, they subconsciously cross it with both war and they cross it with horror films that they've seen in the 1950s.

Stone oversimplifies key issues of the safety of nuclear technology. That applies in particular to waste management, potential accidents, and—most of all—nuclear proliferation. The sloppiness of what he says suggests that he doesn’t know the first thing about nuclear technology. He talks about enriching plutonium. Uranium is enriched, but the process used for plutonium is chemical separation, which is completely different, as explained in more detail in the next section. Stone mentions that building bombs is difficult and that it may take years. Last time I checked, it takes about 7.5 years to build a nuclear reactor and connect it to the electric power grid.

Technical note

If you like, skip the following over-simplified technicalities and fast-forward to the next section.

An atom consists of a nucleus surrounded by a cloud of electrons. The nucleus is composed of nucleons which come in two varieties: protons and neutrons. Each proton has a positive charge of one unit. Electrons have a negative charge of one unit. Let’s consider only electrically neutral atoms, which have an equal number of protons and electrons. For a fixed number nuclear protons, the number of neutrons in the nucleus can vary. This leads to isotopes all with near-identical chemical properties. For instance, uranium has 92 protons in the nucleus and 92 electrons. The most abundant isotopes of uranium is 92238U (aka U-238), where the 238 is defines the total number nucleons. A less abundant isotope is 92235U (aka U-235). Uranium occurring in nature consists for 99.3% of U-238 and 0.7% U-235. The natural abundance of other isotopes is small enough to ignore.

In the following nuclear reaction a single neutron collides with U-235 and splits it. The reaction releases a large amount of energy, roughly one million times as much as a typical chemical combustion reaction:

Apart from the two new atoms, the fission products rubidium (Rb) and cesium (Cs), two neutrons are created. These two neutrons (n), unless they escape, can initiate two more similar reactions, releasing four neutrons, and so on. The result is a chain reaction. If the chain reaction is controlled by removing neutrons, it can be used to generate power in a controlled way. If too few neutrons escape, the result can be a meltdown or, if the circumstances are right, a nuclear explosion.

Most commercial nuclear reactors run on enriched uranium in which the concentration of U-235 is boosted into the 4% to 5% range. Enrichment is a difficult process because uranium isotopes are virtually indistinguishable chemically. Nuclear reactors can also run on naturally occurring uranium. Such reactors require a moderator, a substance that slows down neutrons. This solves the enrichment problem but it introduces other technical challenges.

Except, for instance, in thermonuclear explosions, U-238 doesn’t split, but it can capture a neutron and emit an electron (e) to transmute into neptunium (Np), which further undergoes electron emission to become plutonium (Pu).

Plutonium can be recovered chemically from the spent fuel of nuclear reactors, the so-called backend. Highly enriched uranium was used to produce Little Boy, the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. Nagasaki was flattened with Fat Man, a plutonium bomb. Both the frontend of a nuclear reactor, because it contains enriched uranium, and the backend with its plutonium pose serious proliferation risks. There are many additional nuclear reactions that take place in nuclear reactors. Some of them get in the way of producing bomb grade plutonium. In addition, spent nuclear reactor fuel requires careful handling because of its short- and long-term radioactive nature with time scales ranging from decades to multiple tens of thousand years.

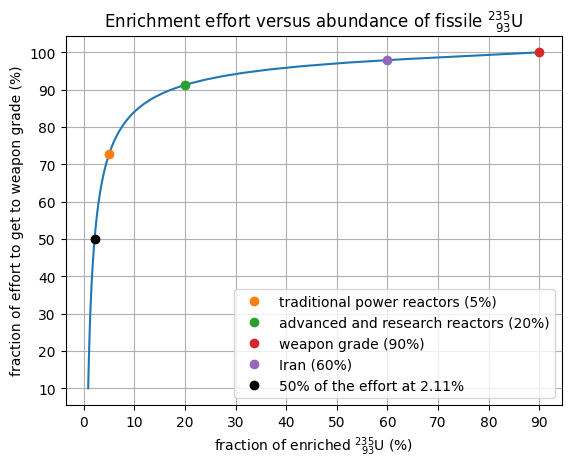

A serious frontend proliferation problem stems from the counterintuitive fact that uranium enrichment from its natural abundance of 0.7% to 2.1% U-235 takes half the effort of bomb-grade enrichment to 90% U-235. Enrichment to 60%, Iran’s current level, completes 98% of that effort, as shown here:

Proliferation danger misrepresented

The understanding of the threat of nuclear weapons and their intimate technological connection with peaceful use of nuclear energy has a long history. The March 1946 Acheson-Lilienthal Report on the International Control of Atomic Energy was mostly a reflection of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s thinking and writing. The report states:

The development of atomic energy for peaceful purposes and the development of atomic energy for bombs are in much of their course interchangeable and interdependent. [emphasis added] From this it follows that although nations may agree not to use in bombs the atomic energy developed within their borders the only assurance that a conversion to destructive purposes would not be made would be the pledged word and the good faith of the nation itself.

In a previous post I quoted Joseph Rotblat, a Nobel Laureate who spent much of his life trying to deal with the dangers of nuclear proliferation. Rotblat addressed the technology, but there also is a major political aspect. The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki destroyed the necessary trust between nations to adhere to international agreements and prevent the conversion of peaceful energy to destructive purposes. As Bird and Martin wrote in American Prometheus, the basis of Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer movie:

MEANWHILE, a group of scientists in Chicago, spurred on by Szilard, organized an informal committee on the social and political implications of the bomb. In early June 1945, several members of the committee produced a twelve-page document that came to be known as the Franck Report, after its chairman, the Nobel laureate James Franck. It concluded that a surprise atomic attack on Japan was inadvisable from any point of view: “It may be very difficult to persuade the world that a nation which was capable of secretly preparing and suddenly releasing a weapon as indiscriminate as the [German] rocket bomb and a million times more destructive, is to be trusted in its proclaimed desire of having such weapons abolished by international agreement.” [emphasis added] The signatories recommended a demonstration of the new weapon before representatives of the United Nations, perhaps in a desert site or on a barren island. Franck was dispatched with the Report to Washington, D.C., where he was informed, falsely, that Stimson was out of town. Truman never saw the Franck Report; it was seized by the Army and classified.

Instead of understanding the need to foster trust between nations, President Truman was overly confident that only the US could master the technology needed to construct nuclear weapons. On October 25, 1945, Oppenheimer had a conversation in the Oval Office with Truman. American Prometheus has this description of the meeting:

At one point in their conversation, Truman suddenly asked him to guess when the Russians would develop their own atomic bomb. When Oppie replied that he did not know, Truman confidently said he knew the answer: “Never.”

Never? On 29 August 1949, the Soviet Union successfully exploded its first nuclear bomb. Obviously, US leadership completely lacked understanding of the nuclear bomb production. To this day, the misconception persists that it requires an effort like the Manhattan Project.

In contrast with Oliver Stone’s claim in the interview mentioned above, the bomb is not really all that difficult to make these days, as R. Scott Kemp mentions in The Nonproliferation Emperor Has No Clothes:

More recently, scholars have represented proliferation rings, illicit trade, and nuclear smuggling as being critical vectors that enable proliferation among the technically weak.

Indeed, less technologically advanced nations have successfully utilized techniques once considered “impossible” for them. For instance, India, Israel, and North Korea have utilized plutonium from the back end of the fuel cycle in reactors that do not require enriched uranium. On the other hand, Iran's approach involves the front-end process of uranium enrichment for fueling nuclear reactors. As Figure 1 of the previous section shows, the uranium enrichment required for peaceful nuclear energy production, corresponds to more than 70% of the work necessary to produce bomb grade uranium.

One might think that the inseparability of war and peace applications of nuclear technology has become obsolete since the Acheson-Lilienthal Report, as mentioned above, flagged it as a crucial issue in 1946. This 2013 National Academy of Sciences report on proliferation risks makes the same point and states:

The material that sustains nuclear reactions to produce nuclear energy can also be used to make nuclear weapons, and so the development of nuclear energy by a non- nuclear weapons state is considered one of multiple pathways to potential proliferation and represents a subset of issues within nuclear nonproliferation.

Here is yet another illustration of the wishful thinking that went into the proliferation chapter of A Bright Future on which Nuclear Now is based:

Decades ago, it was widely feared and assumed that by now dozens of countries would have nuclear weapons, but that has not happened. Nine countries have them, including the problem case of North Korea, but proliferation has not gone beyond that.

This comment has not aged well. Contrast it, for instance, with what Ha’aretz wrote on December 26, 2023:

Iran has reversed a months-long slowdown in the rate at which it is enriching uranium to up to 60 percent purity, close to weapons grade, the U.N. nuclear watchdog said on Tuesday.

Reuters confirmed this report:

Iran already has enough uranium enriched to up to 60%, if enriched further, to make three nuclear bombs, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency's theoretical definition, and more at lower enrichment levels. Iran denies seeking nuclear weapons.

As of the end of November, Iran has been producing nine kilograms of 60% enriched uranium per month, implying that Iran at that time was less than five months away from potentially acquiring a nuclear weapon.

Iraq and Libya previously had nuclear weapons programs but discontinued them. The attacks on these countries might have influenced North Korea's decision to pursue its nuclear weapons program, considering it vital for its national interest.

Iran's situation is more complex. Despite denying the pursuit of nuclear weapons, Iran's enrichment of uranium to 60% stands in stark contrast to the typical 4% to 5% range employed civil nuclear reactors. This high-level enrichment doesn't align with the production of peaceful nuclear energy, and raises significant concerns about Iran’s intentions. This situation underscores how difficult it is to distinguish peaceful and military applications of nuclear technology.

The chapter Preventing Proliferation of A Bright Future has the following to say about nuclear fission, the energy source both of power plants and weapons:

But they are not the same thing, any more than using gasoline in your car is the same thing as dropping napalm, though both use the same basic chemistry.

The gasoline-napalm metaphor is a textbook example of rhetorical diversion, distracting the reader by reciting a trivial, unrelated truth. The result of such gimmicks is a superficial, incomplete and overly optimistic way of dealing with the risk of nuclear proliferation.

It is extremely disconcerting that media interviewers and reviewers also fail to recognize and flag Nuclear Now’s blatant misrepresentations. Explore the following links and check for yourself: Al Jazeera, Business Insider, Jacobin, New York Times, etc. None of these media outlets ever mentions the risk of proliferation.

Price–Anderson Nuclear Industries Indemnity Act

The Congressional Research Service describes this act as follows:

The Price-Anderson Act’s limits on liability were crucial in establishing the commercial nuclear power industry in the 1950s. The nuclear power industry still considers them to be a prerequisite for any future U.S. reactor construction.

As mentioned in a previous post, a notable summary of this legislation comes from former Vice President Cheney:

“It needs to be renewed,” Cheney said. “If it is not,” he said, “Nobody's going to invest in nuclear power plants.”

In other words, if the people don't pay the insurance bill for the nuclear industry, the venture capitalists won't play. Another reauthorization and expansion of the Price-Anderson Act is a currently under discussion in Congress. Yet, this vital fact is missing in Nuclear Now.

A German insurance company estimated that If the nuclear energy sector had to pay its own insurance, the price of electricity might increase by a factor of 200.

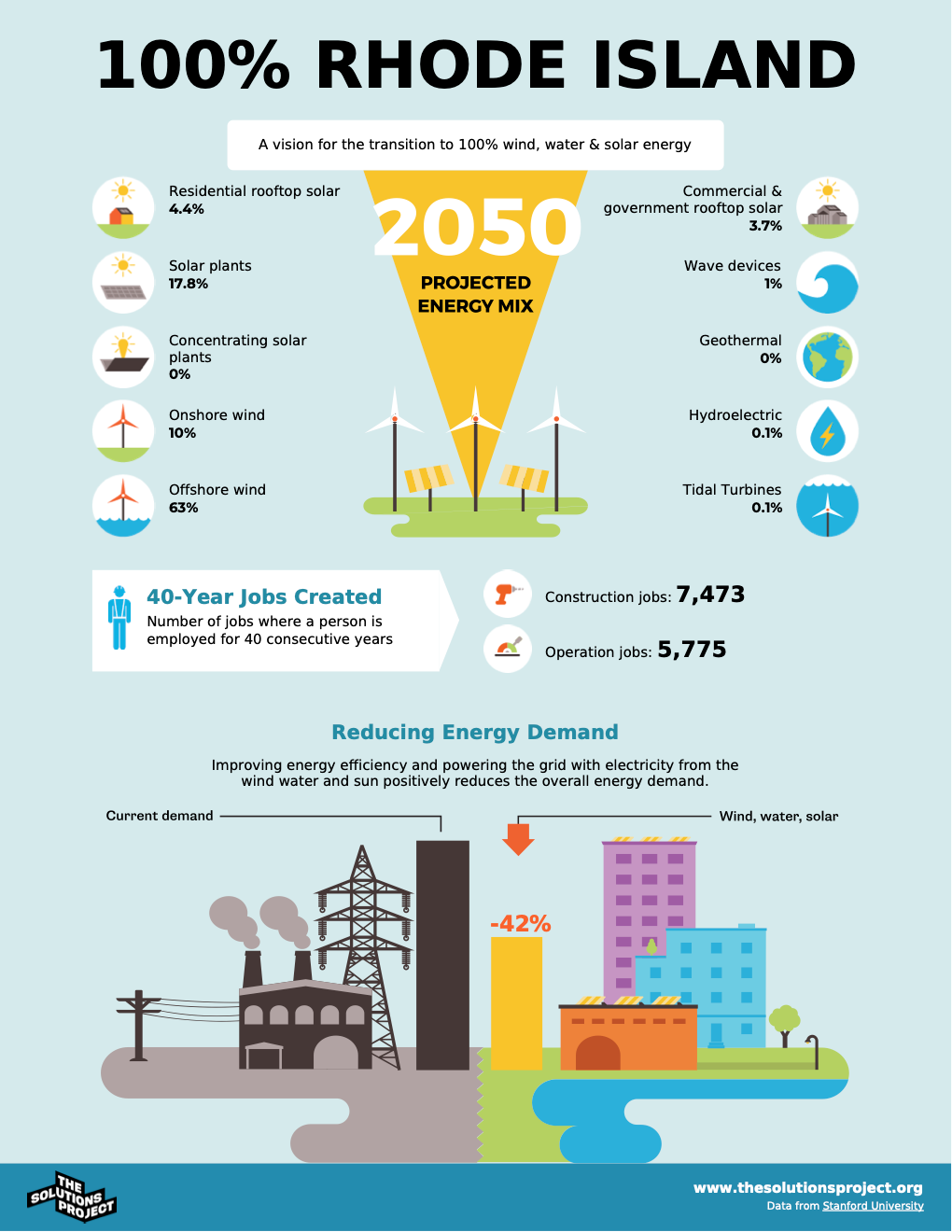

Solutions Project

The Solutions Project has worked out detailed plans for a transition to 100% wind, water and solar energy. Follow this link for an interactive map show the specifics for countries, cities, and US states. This is what the solution for Rhode Island looks like:

Nuclear energy is not part of the proposed mix. Zip, zero, zilch! This shows that Nuclear Now is a dangerous solution for a problem that not even exist.

Advanced nuclear reactors

Chapter 12 of A Bright Future is called Next-Generation Technology, aka the fourth generation. It is not a serious discussion of the issues, but rather reads like a collection of commercials, for instance for Terrestrial Energy, NuScale Power, Bill Gates’ Terrapower, and so on. For a serious discussion see Advanced Nuclear Reactors: Technology Overview and Current Issues produced by the Congressional Research Service. This quote succinctly sums up the issues:

Not all observers are optimistic about the potential safety, affordability, proliferation resistance and sustainability of advanced reactors. Because many of these technologies are in the conceptual or design phases, the potential advantages of these systems have not yet been established on a commercial scale.

France faced technical problems in its nuclear plants, leading to a decline of more than 20 percent in nuclear power production between 2021 and 2022.

Nuclear energy going global

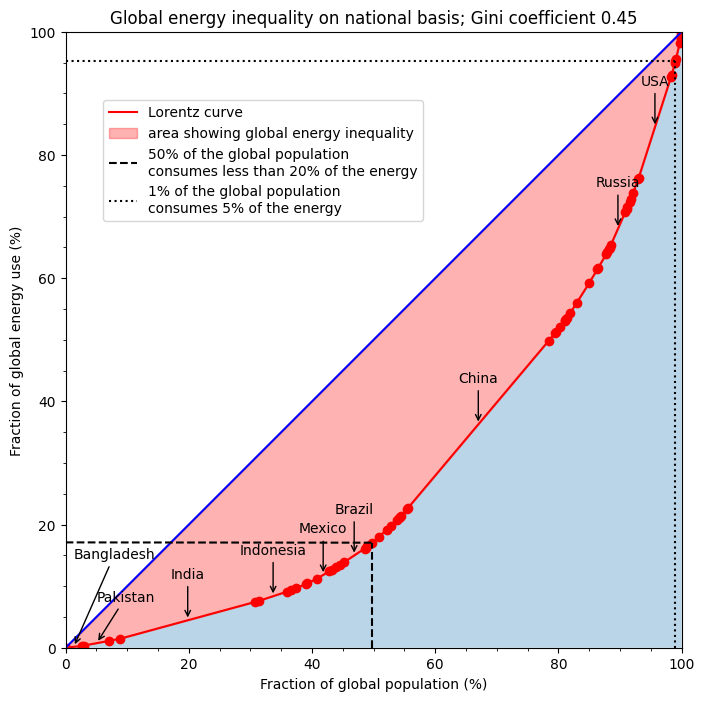

Energy use per capita varies vastly from one nation to another. In Figure 2, nations are arranged according to increasing per capita energy use. Pick a point along the horizontal axis, for instance the point at 50%. It refers to the 50% of people in the world consisting of the ones with the smallest per capita energy use. Follow the dashed line up and then to the left, as shown. It intersects the vertical axis at a point a little less than 20%. This means that the 50% of the people in countries with the lowest energy consumption together consume less than 20% of the total global energy. Now consider the dotted line up from 99% on the horizontal axis and over to 95% on the vertical axis. This means that the lowest 99% of energy consuming countries consume only 95% of the total energy.

Figure 2 does this for many countries across the globe. This produces the red, so-called Lorentz curve. The Gini coefficient of 0.45 in the title of the chart indicates high inequality. For additional details see Large inequality in international and intranational energy footprints between income groups and across consumption categories.

To supply the people across the world the same per capita power as is enjoyed in the US, the global power supply would have to be tripled. As their goal, 22 countries at COP28 declared that they want to see nuclear power capacity tripled by 2050. The combined result this tripling and the creation of energy equality across the globe is likely to result in an almost ten-fold increase in global nuclear power supply. What will that do to:

the proliferation risk?

the risk of nuclear accidents?

the nuclear waste problem?

To ask these questions is to answer them: these risks will probably increase by an order of magnitude.

Furthermore, 97 days have passed since the latest flare-up of the conflict in Palestine-Israel. During that time—97 days—77,600 people in the US have died due to poverty, averaging 800 victims a day. The silence surrounding this issue is a disgrace for the nation, as are its warped priorities.

Burton Richter, experimental high energy physicist and 1976 Nobel laureate wrote in 'Beyond Smoke and Mirrors:'

"The scientists and engineers know that a major strengthening of the defenses against proliferation is a political issue, not a technical one. The politicians hope that some technical miracle will solve the problem so that they won’t have to deal with political complications, but the scientists know that this is not going to happen."

'Nuclear Now' simply skips over the whole issue and nobody in the media seems to notice. It seems that collective, Hollywood-enhanced stupidity is not recognized as the existential threat it poses.

Peter, it might be more effective in convincing MANY MORE people of your main point if you declared FIRST that nuclear weapons can be produced relatively quickly from nuclear reactors THEN explain why. ❤️🙏🏼